Formula 1 returns to Las Vegas this weekend, a reminder of how different the sport looks today compared to the early turbo era. Carbon-fiber hybrids cutting through night street lights has nothing to do with the wild, experimental world of the early 1980s—an era when BMW won its first and only Formula 1 World Championship. That lone title came in 1983 with Brabham and Nelson Piquet, powered by a 1.5-liter BMW engine that became one of the most extreme powerplants the sport has ever seen.

From a 1960s Road-Car Block to the Turbo Era

The basis of BMW’s title-winning M12/13 engine traced back to the M10, a simple iron block first used in the early 1960s. It was never designed for Formula 1, let alone for the absurd boost pressures of the early turbo era. But the block was strong, stable, and familiar to BMW’s engineers. Paul Rosche and his team turned it into something completely different: a compact engine capable of producing astonishing power without disintegrating—at least most of the time.

Stories from the period describe BMW pulling old M10 blocks from high-mileage road cars because the metal was already “aged” from years of heat cycles. Whether myth or truth, it captures the reality of the program: BMW was building a jewel-like race engine.

The M12/13: Fast, Fragile, and Occasionally Terrifying

By 1983, BMW’s turbo engine had developed a reputation for two things: extreme power and unpredictable behavior. The single large KKK turbocharger produced huge lag, followed by a violent hit of boost. Drivers had to anticipate the power delivery rather than react to it. The engine was a handful to drive.

In qualifying trim, the M12/13 likely exceeded 1,200 horsepower. No dyno in BMW’s shop could measure the full output; the needle simply ran out of scale. But power alone wasn’t enough. Reliability was the weak spot, especially early in the season. Engines sometimes lasted only a few laps at full boost, and Brabham’s mechanics spent long nights swapping out components with almost no margin for error.

Still, when it held together, nothing on the grid could match its straight-line speed.

Gordon Murray’s BT52: Built for a New Rulebook

The 1983 season introduced new regulations that outlawed the dramatic ground-effect tunnels of previous years. Designers had to start over. Gordon Murray, Brabham’s technical director, used the rule change as an opportunity. The result was the BT52, a narrow, sharply tapered car designed around the BMW turbo engine. Murray moved the weight as far rearward as possible to help traction under full boost. The car ran light fuel loads and used mid-race refueling—unusual at the time—to keep it nimble. It wasn’t the most forgiving car on the grid, but when the balance was right, it was brutally fast.

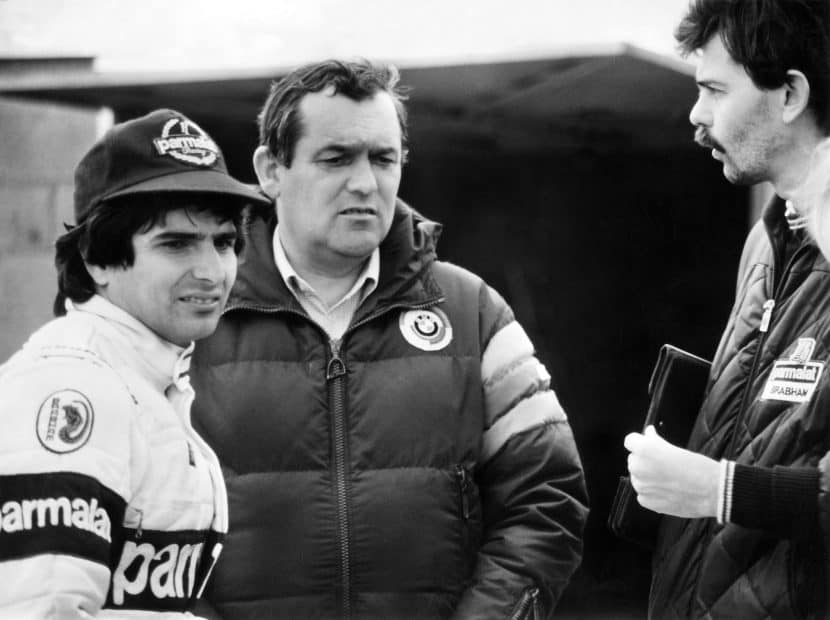

Nelson Piquet: The Driver Who Could Handle It

The BT52 demanded a calm, mechanically minded driver. Nelson Piquet was exactly that. He understood the engine’s behavior, knew how to manage temperatures and boost pressure, and never panicked when the power came in late and hard.

The 1983 championship battle originally looked like a Renault–Ferrari fight. Renault started strong with Alain Prost leading the points early, and Ferrari had the most reliable package. Brabham and BMW struggled with DNFs and inconsistent form. But as the season progressed, the BMW engine became more dependable, the BT52’s setup improved, and Piquet began clawing back points.

The turning point came at Monza, where Piquet’s top-end speed overwhelmed the competition. From that moment, the title fight shifted. Renault faltered late in the season, and by the final round at Kyalami in South Africa, Piquet had a real chance. He didn’t need to win—he simply needed to finish ahead of Prost. A measured drive to third place sealed the championship.

It was the first time a turbocharged engine had ever won the Formula 1 World Championship.

Why the 1983 Title Still Stands Out

BMW returned to Formula 1 later with Williams in the 2000s and then as a works team with Sauber. They had fast cars, pole positions, and even a legitimate title shot in 2008. But nothing matched 1983. That season remains BMW’s only F1 championship and one of the defining moments of the early turbo era.

It happened because an old block proved tougher than anyone expected, because an engineering team took risks most manufacturers would avoid, because Gordon Murray built a car around the chaos, and because Nelson Piquet understood how to drive a machine that rewarded precision rather than aggression.

As Formula 1 races under the lights of Las Vegas, with hybrid systems and software dictating the limits, it’s hard not to appreciate how raw and improvised 1983 really was. Forty-plus years later, it remains one of the most interesting chapters in BMW’s racing history—and the one time Munich reached the top of Formula 1.