BMW was involved in Formula One (F1) for nearly two decades. Their stint started as an engine supplier to Bernie Ecclestone’s Brabham team in 1982 but it wasn’t before 2006 that the company became an official F1 constructor when it acquired the Sauber F1 Team. However, following the global economic crisis, BMW was forced to pull out of the sport in 2009. What follows is a history of the German manufacturer in F1.

Engine Supplier in the 1980s

In 1982, the Brabham Team, owned by Bernie Ecclestone, started using BMW engines after the two parties signed a deal in 1980. Development of the engine took time but BMW made an admirable start to its F1 career with its first win coming at the 1982 Canadian Grand Prix when Nelson Piquet took home the Checkered flag. The following season, BMW-powered Brabham BT52 helped Piquet win the Drivers’ Championship.

The engine supplied by BMW was a 1.5-liter M12/13 turbocharged straight-4. It was based on 1,499 cc M10 engine block that initially produced just 80 bhp when it was first introduced in 1961 in the Neue Klasse series. At that time, the turbocharged engines had a 1.5-liter limit in F1, so the M10 became a good foundation to work upon. The M12/13 was initially used by BMW in Formula Two but looking at Renault’s success with the fist turbocharged engine in F1 that they introduced in 1977, BMW decided to enter the arena.

By 1985, the M12/13 engine was producing more than 1,350 bhp in qualifying- that’s ludicrous amount of power even by F1 standards. In fact, Paul Rosche, who is labeled by BMW as the “father” of the Championship engine, admitted that BMW did not even know how much power the engine could produce. “It must have been 1,400 bhp, but we don’t know the exact figure since the engine dynamometer didn’t go beyond 1,280 bhp,” he once stated.

Nonetheless, the M12/13 engine is widely considered as the most powerful F1 engine to have been ever produced. However, it faced reliability troubles. For example, in 1984, Piquet managed to get the pole nine out of 16 times with his BMW-powered Brabham BT53, but he had to retire in more than half of the GP’s during the season. Consequently, Piquet ended the calendar in fifth place- a dismal position considering how well he did in the qualifying.

The fuel consumption of these cars was high (which became a problem as F1 started to introduce limits on fuel usage) and engine blow-ups and turbo failures were common. In addition, the turbo lag meant BMW’s turbocharged cars lost out to the normally aspirated cars on the slower bends.

A reason for BMW engines blowing up could be that they deliberately chose engine blocks that had done up to 100,000 kilometers. The idea was if an engine block had to break, it would have done so already. Meanwhile, after Brabham, Arrow and Benetton also started using BMW engines.

Arrow first got a taste of the BMW turbocharged M12/13 in 1984. They finished ninth in the Constructors’ Championship that year and eighth the following season. Benetton used the BMW powered cars during their first season in F1 (1986) and they won the Mexican Grand Prix that year. Although Benetton switched to Ford in 1987, the raw pace of the BMW engines in their cars was enthralling. At the 1986 Italian GP, Gerhard Berger’s Benetton B186 recorded the fastest straight-line speed by a turbocharged car (351.22 km/h) in the “first turbo era”.

In 1986, BMW also started to tilt their engines by 72 degrees in Brabham cars but the design failed due to “cooling issues in the tight compartment”. That year, however, the company also announced that it would leave F1 at the end of the 1987 season.

Arrow were still keen to use the M12/13 so they brokered a deal to use its uptight version in 1987 and 1988. They badged the engine “Megatron”. The two years proved to be Arrows’ best years in F1. Despite continual technical limitation on the use of turbo owing to safety concerns, Arrows finished sixth in 1987 and fifth in 1988. In 1987, “Megatron” was also used by Ligier but it went out of business at the end of the 1988 season after turbocharged engines were banned in F1.

Williams-BMW Partnership

At the end of the 1998 season, Williams lost their designer Adrian Newey to Mclaren and their engine supplier Renault decided to quit F1. Williams’ partnership with Renault commenced in 1989, yielded them four Drivers’ Championship and five Constructors’ Championship. Two of the Renault-powered cars, the Williams FW14B and FW15C are considered the “most technologically advanced cars” to have ever raced in F1.

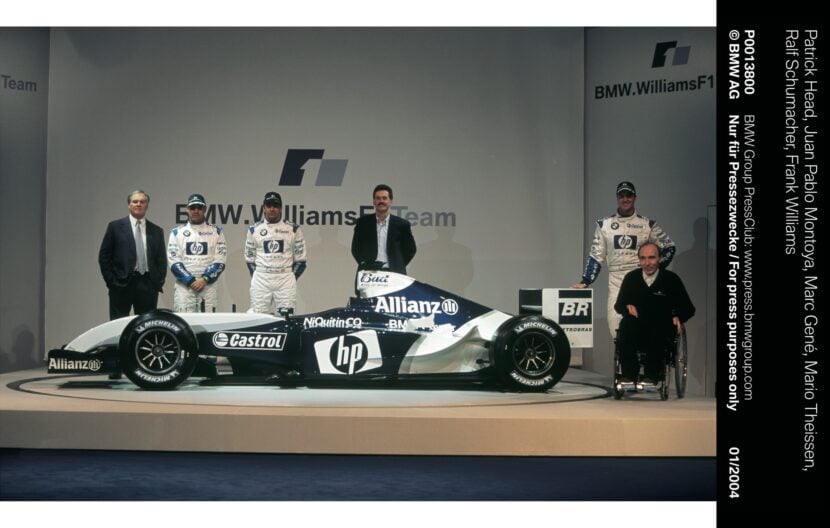

Renault’s exit meant Williams had to look for a new engine supplier and they agreed a six-year deal with BMW in 1999. As per the agreement, Williams were to have a German driver in their team, which led to their signing of Ralf Schumacher in 1999.

After testing in 1999, during which Williams used Supertec engines, BMW-powered cars returned to the track in 2000. It was a lackluster season with no wins but the team improved the following year with the duo of Schumacher and J. P. Montoya taking the driving seats. The car, FW23, featured a normally aspirated V10 motor that could produce 830 bhp and led Williams to four wins, including their first triumph at Imola since 1997. Yet, despite finishing third in the Constructors’ standing, Williams couldn’t mount a title challenge owing to the unreliability of the BMW engines, with the cars exhibiting a finishing rate of less than 50 percent.

In 2002, further improvements were carried out by BMW and Williams finished second that season. The raw pace of the BMW engine helped Montoya to five consecutive poles at one point during the season. The Colombian driver even notched the fastest lap in the history of F1 during that year, at Monza, Italy. Montoya averaged a speed of 256.8 km/h during the lap with the car revving up to 19,000 rpm.

After the qualifying, BMW Motorsport Director Mario Theissen was quoted as saying: “For an engineer it is thrilling to see figures which not so long ago were considered unattainable, suddenly becoming reality.”

Williams won just one race that season but that isn’t bad considering only two races were won by a non-Ferrari driver. Impressed by BMW’s engineering, talks of contract renewal started.

In 2003, the BMW-Williams partnership hit the peak of their success. With a more powerful engine, the team won four races and Montoya finished third in the Drivers’ Championship. Williams came second in the Constructors’ standing and despite the monstrous engine, the design of the car (FW25), was surprisingly criticized by the drivers and BMW engineers for its poor aerodynamics and handling. In one instance, BMW workers put up a picture of a tortoise on the inside of one of their trucks, suggesting it was the FW25.

Nonetheless, in June 2003, Williams and BMW agreed to extend their partnership till 2009. Williams aimed to get access to a “deeper pool of BMW resources” and the German company looked to provide more expertise and assistance from their Munich F1 facility.

From 2004, the performance of Williams started to decline and BMW became increasingly critical of its partner’s inability to produce a Championship wining car. The relationship between the two sides strained as their feud became public.

“Our partnerships in the past with Renault and Honda have been more successful and co-operative,” Frank Williams told Autosport magazine in June 2005.

“You never had this constant finger-pointing. We do not constantly ask why BMW had some 150 engine failures in 2000 alone.”

It wasn’t long before the result-hungry BMW decided to part ways with Williams and start their own F1 team. They initially tried to purchase Williams but their approach was refuted and the company eventually settled for Sauber.

BMW Sauber

In Summer of 2005 BMW acquired a 80 percent stake in Sauber for a reported $100 million. As per the agreement, the engine was to be designed at BMW’s headquarters in Munich, while Sauber’s Hinwil factory was used for chassis construction and wind tunnel testing. The livery of the cars showcased the traditional BMW white and blue color-combination with a touch of red.

Petronas and Credit Suisse- Sauber’s sponsors, signed deals with BMW while the latter also agreed a “technical partnership” with Intel.

Frankly, BMW Sauber didn’t do really well. They won just one race over four seasons, although the team did manage a podium finish 17 times. They helped Robert Kubica and Sebastian Vettel enter the foray of F1 too but the two players achieved most of their success after leaving BMW Sauber.

Kubica, in fact, was critical of the lack of development by the team during the 2008 season, when their first win came in Canada.

Before the start of the 2009 season, BMW hoped to challenge for the title. They focused extensively on better aerodynamics and their cars featured a double-check diffuser. Yet, the team was off to a mediocre start and couldn’t even accumulate ten points by mid-season. The new technical regulations also halted the BMW’s progress and with the financial meltdown making the company vulnerable to huge losses, in July 2009, they announced their decision to leave F1.

Since then, they have been out of the game. It was rumored last year that BMW might make a comeback but the claims were denied by the company.