I had become aware of the i3 and i8 projects some time before heading to Sweden for a two week training assignment in March 2011. By happenstance the routing from Sweden back to the U.S. gave me a two hour layover in Munich. With a call to the company’s travel agency, that two hours became five days.

The last time I had been in Munich was 1968 and I distinctly remembered, as a 15 year old, sitting in the Augustiner Keller having lunch, with a halb Helles to wash it down with. I really wanted to be back in Munich, and not just for the gemütlichkeit, but for the BMW experience – having spent the last three years, since mid-2008, enjoying a BMW 135i.

Thanks to BMW NA’s Communications team, I got to sit in on Innovation Day 2011, and also got a chance to visit the FIZ (Forschungs und Innovationszentrum). It was during the brief tour of the FIZ that we happened to wander past a partially covered i3 ‘life module’ – passenger shell. This was April 2011 and they had a glued up i3 module right there in the aisle. Understand though, when you visit a manufacturer’s research and development facility you don’t see anything ‘accidentally’, you see exactly what the manufacturer wants you to see. Interesting, here was a carbon fiber space frame for a car that would be built in the thousands. How in the world were they going to pull that off using the existing CFRP processes.

Having seen the i3 passenger shell, I was looking forward to the press roll-out of the prototypes scheduled for the end of July 2011. I was hoping to get a better understanding of how they intended to build these CFRP machines. When the invite to see the i3 and i8 prototypes unveiling in Frankfurt came, I was in the middle of preparation for a training gig in Puerto Rico (good food, good people, and a good local beer – Medalla), I accepted it knowing that I would have less than 24 hours on the ground in Frankfurt.

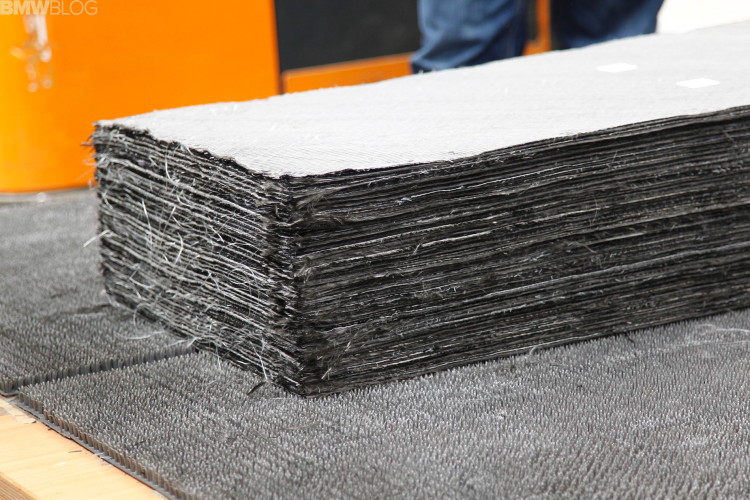

I had, long before that time, seen the typical build up of a carbon fiber race car – a Society of Automotive Engineers Formula SAE project. The process involved laying up sheets of woven carbon fiber cloth that has been pre-impregnated with resin – the cloth has to be kept refrigerated prior to use in order to keep the resin from losing its effectiveness. The part is formed, laid up, in a ‘female’ mold and then placed in a large plastic bag. A vacuum is pulled in the bag to remove any potential air bubble from between the layers of carbon fiber cloth – air bubbles will weaken the part.

The hermetically sealed bag, with part enclosed, is then placed in an autoclave and subjected to heat and pressure. An autoclave resembles an ‘iron-lung’, for those of you old enough to remember the scourge of polio, but maybe a better analogy is it is a REALLY BIG pressure cooker. Several hours later, you pull out and trim the appropriately stiff and finished part.

Producing a CFRP part using this process takes a lot of time – and a lot of energy. Great for small batches of cars, where price is no object, but not a model for mass production. Impractical for cars built in thousands of units as opposed to dozens of units. So it was with no small amount of intrigue that I listened to the pitch regarding how the i3 would be built in quantity using CFRP. I had a chance to ask a few questions of the production folks and learned that BMW would use a process called resin transfer molding (RTM) to produce the i3’s and i8’s space frame panels.

RTM was in use in a number of industries, but it was used primarily for fiberglass molding, not CFRP. In the fiberglass industry it sometimes is considered a solution for medium volume production, according to one source that means up to 10,000 parts per year, with hand lay-up, and specialized high compression molding machines. Mold life is not especially long – which is expressed in the number of parts that can be pulled before the mold can longer deliver a part within tolerances – according to a number of sources. The longevity of molds (the equivalent of a die in a metal stamping process) was an issue that BMW had to reckon with in relying on RTM for CFRP production.

Additionally the optimum viscosity of the resin and how to quickly flow the resin through the carbon cloth would have to be determined, and for each specific part possibly. BMW uses a proprietary resin and uses vacuum in conjunction with high pressure resin injection into the mold to deliver a consistent process. Once the resin has penetrated the entirety of the piece, it can be cured in situ.

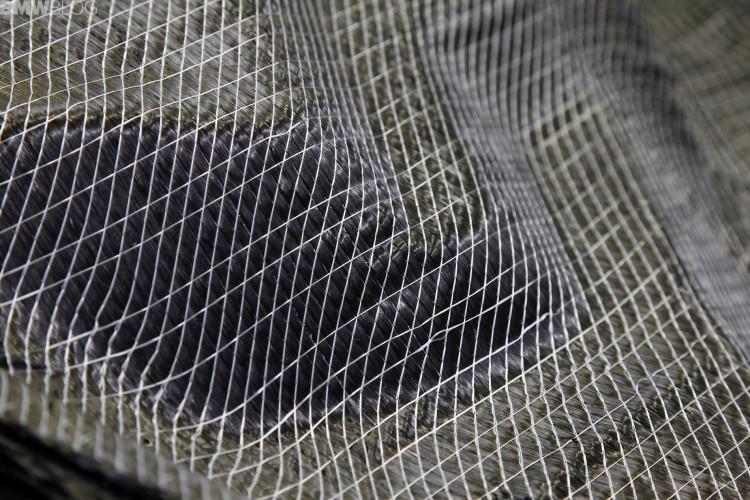

I had written, at one point, that the carbon fiber was woven. Turns out that’s not the case and not being woven is critical to how the process of molding CFRP panels has been sped up. Stitching together, sewing into parallel pieces, long strings of CFRP, we believe, facilitates optimal flow of resin through the parts, shaving precious time off the process. Bear in mind, the longer it takes to finish a part the more ‘parts making machinery’ you will need for a specific quantity of parts. And with CFRP, the quicker you get raw material to finished parts the less energy you use and the more money you save.

There were scores of issues that had to be sorted out to make this process work, and BMW had been working with the process for about 10 years (starting with the CFRP roof panels for M3s). Yet, making this work for tens of thousands of vehicles undoubtedly lead to many sleepless nights and more than a few gray hairs for engineers and management. But, they persevered and subsequently now find themselves alone in front of the industry. A BMW person told me that it would take at least five years for other manufacturers to catch up to where BMW is and then they’d have to carefully review the patents. (You don’t think BMW didn’t protect their interests when they developed this process, did you?)

I wrote in 2011, “CFRP is a key enabler for the ‘i’ sub-brand and, as the production processes and supply of the raw material improve, expect to see more structural CFRP in the mainstream brand.” And now, with the reveal of the Vision Future Luxury Concept, we see where BMW is headed with its mainstream products. Steel, and aluminum, are not dead yet – BMW has made a significant investment in metal pressing components in the recent past, so don’t expect the next generation M3 to be made with a aluminum frame and carbon fiber body. But don’t be surprised if the generation after that is.

As an aside, and something that I think would be really fun to drive, in a number of press events involving the i3 and i8 I have remarked to various BMW managers and PR people that my ideal car is just begging to be built using an i3 sized aluminum chassis and a coupe CFRP space frame that would then use the IC engine from the BMW 1600 GT motorcycle. A new BMW 700! My suggestion, so far, has been unheeded – probably just as well for the share price that it isn’t heeded. I can dream though, can’t I?