This year marked our third time joining BMW for its annual Responsibility Days, following previous editions in South Africa in 2023 and San Luis Potosí, Mexico in 2024. The program is BMW’s way of opening its doors to show how the company is handling sustainability, workforce development, and industrial transformation across different regions. Each year focuses on a different plant and a different set of challenges, offering a direct look at how BMW’s long-term strategies translate into day-to-day operations.

The 2025 edition took place in Munich, where BMW is in the middle of one of the most complex restructurings in its global manufacturing network. But before visiting the plant, the program began the night before at Munich Urban Colab, a shared innovation hub BMW uses to collaborate with startups, universities, and city partners. Instead of presentations or product reveals, the evening showcased companies working with BMW on materials and processes meant to reduce emissions and close resource loops in production.

Natural-Fiber Components Coming to BMW Cars

One of the suppliers on display, BComp, develops natural-fiber components that could replace carbon fiber in future applications. BMW also showed an iX3 seat built entirely from renewable or recycled materials, part of its circularity targets for future models. BMW also showed the new iX3’s frunk design, noting that the structure is built from recyclable materials as part of the brand’s circularity strategy.. Nothing shown that night was theoretical; these were early-stage solutions already being tested and evaluated for real industrial use.

The session set the tone for the next day, when we moved from prototypes into the places where BMW now has to implement these ideas at scale — the Munich plant, the Talent Campus built on the former engine plant footprint, and the Robotics and AI Training Center, where BMW is preparing its workforce for new manufacturing processes.

BMW Munich Plant: A Factory Rebuilt While Its Pulse Keeps Going

The Munich plant is in the middle of one of the most extensive rebuilds in BMW’s manufacturing network, and the work is happening while the factory continues running at full speed. More than 6,500 employees from over 60 countries keep the line moving, and a new vehicle leaves the line roughly every 60 seconds. In 2024, the plant built more than 83,500 fully electric BMW i4 models, showing how quickly EV production has scaled inside a site originally designed for combustion engines.

The challenge now is preparing the plant for the Neue Klasse, which begins production in 2026, without shutting down operations. Because the site is located in the middle of Munich and has no room to expand outward, BMW has to rebuild from within. Around 33 percent of the existing structures will be dismantled, and roughly 600,000 tons of material must be removed as older buildings come down. At the same time, BMW is adding about 70,000 square meters of new floor space, contributing to a total of 250,000 square meters of new gross floor area once the project is complete.

The new production halls are being designed as three-story buildings for assembly and body shop operations, a vertical approach needed to increase usable space on a plot that measures just 500,000 square meters but already contains over 620,000 square meters of production area through stacked layouts. BMW has set an 18-month timeline from the start of deconstruction to the point when new technology must be installed for the Neue Klasse. To clear space, the company is carrying out 13 major relocations, shifting equipment, logistics routes, and departments into temporary areas.

The logistics involved in keeping the plant operational while construction advances are substantial. Approximately 400 trucks move in and out of the facility every day, transporting debris out and bringing construction materials in. BMW says the new structures will meet an energy standard of 40 percent of the reference value, part of a broader effort to reduce emissions across its production network. Overall, there are 800 trucks moving in and out of the plant every single day, including trucks transporting parts or cars.

Few automotive plants attempt a transformation of this scale without pausing production, and Munich’s constraints make the project even more complex.

Later in the morning, during a roundtable discussion, Ilka Horstmeier, BMW’s Board Member for People and Real Estate, offered a description that aligned exactly with what we had seen.

“It’s like an open-heart surgery every day,” she said. “We are transforming this plant while we are producing 1000 cars per day. It’s a logistical masterpiece… and that’s the way we run transformation at BMW — people, places, production systems. We think them all together.”

She spoke with the kind of candor that comes from managing the human side of change as much as the operational side. Nowhere was that clearer than when she discussed the closure of the Munich engine plant, which had operated for more than seventy years. The transition required relocating or reskilling 1,200 employees — people whose identities were shaped by building combustion engines, from four-cylinders to V12s.

“There was also bad news,” Horstmeier said. “People like their jobs. They like to produce eight-cylinders, twelve-cylinders. But we managed that.”

She described how BMW created individualized paths for every employee, mapping out what their first day, first week, and first month would look like. Her takeaway was simple: “Trust is maybe the most valuable currency in these transformative times.”

Inside the Talent Campus: Training for a Workforce That Has to Transform Quickly

After the plant tour, the program moved a few minutes down the pedestrian walkway to BMW’s new Talent Campus, built on the footprint of the former Munich engine plant. The facility is now the central training hub for roughly 40,000 BMW Group employees in Munich, and it reflects the scale of the company’s workforce transition more than any presentation could. BMW has invested more than €1 billion in training and development over the past three years, and the Talent Campus shows where that money is going.

BMW currently brings in around 1,200 vocational trainees every year, spread across 30 different training professions and 18 dual study programs. Recruiters told us the talent pipeline has changed significantly in the past decade. The company now relies on new recruitment channels, early engagement with students, and closer relationships with vocational schools and universities to secure young technical talent. Apprentices are brought in earlier, retained earlier, and given clearer development paths than in the past. The aim is not just to fill open roles but to build a workforce capable of adapting as production methods evolve.

The training ecosystem behind the Talent Campus is global. BMW runs vocational programs in 20 manufacturing locations and branches worldwide, with the largest networks in Germany, the UK, the U.S. and Hungary. Germany alone accounts for around 3,865 trainees, supported by partnerships with 66 schools, including 33 vocational schools and 8 universities. Across the broader network, BMW works with colleges in the U.S., the UK, Brazil, Thailand, China, and Hungary, along with vocational-technical schools in Austria and Mexico. In total, the company estimates about 1,163 trainees are active across its global Rolls-Royce and BMW Group locations.

Inside the Munich Talent Campus, the shift in training philosophy is immediately visible. Traditional workshop areas sit alongside digital training labs, robotics stations, automation systems, and dedicated spaces for AI-based tools. Apprentices rotate between VR welding simulators, robotic workstations, 3D printing areas, Microsoft Hololens environments, and CNC machining setups. Trainers refer to this as “future skills” development — not just teaching a trade, but teaching employees to navigate technology that evolves every year.

BMW says more than 75,000 employees per year take part in qualifications related to emerging fields such as high-voltage systems, digital production tools, and EV-related processes. More than 50,000 employees have already completed training specific to e-mobility. Much of this work is done in cooperation with universities, technology partners, and other industrial companies. Internally, BMW uses the Talent Campus to pilot new instructional methods before pushing them out to other plants worldwide.

Robotics and AI: Practical Tools Already Embedded in the Factory

The final stop of the day, the Robotics and AI Training Center, offered a view into how digitalization is unfolding inside BMW’s plants. Instead of the large industrial robots often associated with automotive manufacturing, we saw collaborative robotic arms being trained for specific tasks — light, flexible machines meant to assist workers rather than replace them. Employees learn how to program these units, how to troubleshoot, and how to adapt them to workstations where repetitive strain or precision requirements make automation useful.

AI made an appearance, but again, not in a futuristic or abstract way. We observed systems used to analyze ergonomic posture by tracking the human body through movement, a method originally developed for motion capture studios before being adapted for workplace assessment. BMW uses these measurements to redesign stations and reduce physical strain. In other rooms, defect-detection algorithms were demonstrated — tools that support human inspectors by catching anomalies the eye may miss.

The consistent message was that AI functions as an assistant rather than an authority.

BMW repeatedly stresses that its long-term competitiveness depends on lifelong learning, and the structure of the Talent Campus makes that point clear. The company is not training employees for one job title or one phase of the industry. It is trying to prepare them for a manufacturing landscape that will continue changing as electrification, software integration, and circular production reshape the work done inside BMW’s plants.

A Strategy That Adapts Instead of Predicts

One thread running through the presentations was BMW’s refusal to commit entirely to a single technological outcome. Horstmeier expressed this plainly during a strategic discussion, acknowledging the uncertainties facing the industry. “We don’t put all eggs in one basket,” she said. “Times are volatile… The prerequisites for 100% electric even in Europe are not there and will not be there until the 2030s.”

Her point wasn’t anti-electric. It aligned with what we saw in the past: factories being redefined so it can handle new electric platforms while still supporting combustion-engine lines for markets that need them. BMW’s approach isn’t about guessing the future; it’s about building flexibility into the system so the company can move with it.

A Transformation Held Together by People

By the time we left the robotics center late in the day, the common thread was quite obvious. All the new technology, infrastructure, and construction mattered, but what tied the entire event together were the people doing the work.

Horstmeier returned to this point repeatedly: “Transformation with our people is possible,” she said earlier in the day.

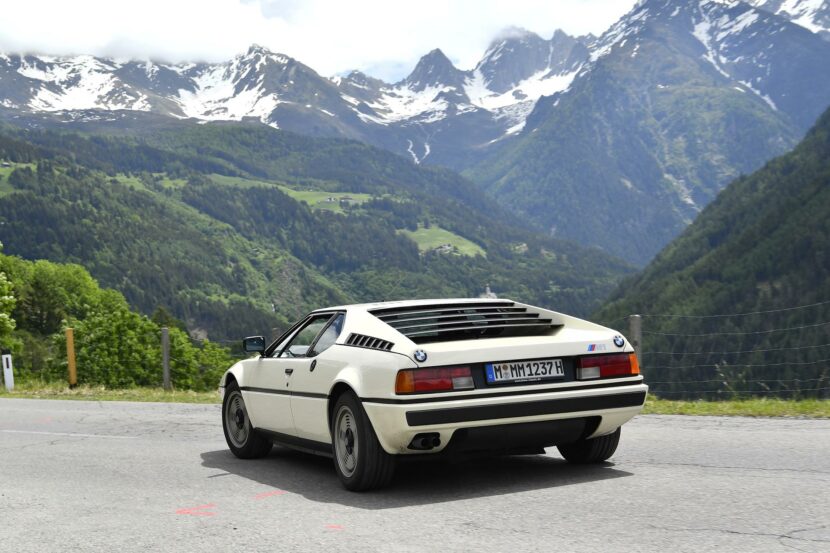

BMW Classic: A Look at the Art Cars and the Cultural Side of the Brand

The first day concluded at BMW Group Classic, where the company shifted the focus from production and training to its long-running cultural programs. BMW used the setting to highlight the Art Car collection, a project that dates back almost five decades and has involved artists from around the world.

Thomas Girst, BMW’s Head of Cultural Engagement, walked us through the history of the Art Cars and explained how the program has evolved alongside the brand. Girst presented two significant pieces from the collection: the Alexander Calder Art Car, the first vehicle created for the series in 1975, and Art Car No. 20, designed by Julie Mehretu and unveiled earlier this year.

Girst emphasized that the Art Car project has never been about marketing but about long-term collaborations with artists who reinterpret BMW’s design language through their own lens. Seeing Calder’s original work next to Mehretu’s latest entry underlined how the program has maintained continuity while allowing vastly different artistic approaches.

The visit added a cultural dimension to the Responsibility Days program, showing how BMW frames its industrial transformation within a broader context that includes design, heritage, and artistic partnerships. Stay tuned for the third installment of the BMW Responsibility Days which includes a visit to the new battery plant in Irlbach-Straßkirchen, followed by a last stop in Landshut.

[Photos: Rainer Haeckl © BMW AG]